I. Introduction

Processes are important pieces in modern society and they help controlling, documenting and standardizing the interactions between businesses, consumers, governments, individuals and other organizations. Tasks, roles, artifacts, goals, rules and their relationships are central abstractions that processes use to determine stepwise recipes used by individuals and systems when navigating through a procedure, such as Claiming Insurance or Buying Airline Tickets.

Processes eventually are materialized, by some explicit representation, to organize activities, coordinate the enactment and analyze its results. Process modeling languages are the notations used to represent processes, whoses more popular examples are BPMN (Business Process Management Notation) and CMMN (Case Management Modeling Notation). The materialized process is known as process model and it can be fed to a workflow automation plataform for automatic or semi-automatic execution, analysis or simulation.

Processes can be found in “simple scenarios” such as in our daily visit to a coffee-shop, where baristas are prepping several different types of Lattes, Cappuccinos, Macchiatos, Iced Coffees, etc. Each order follows a combination of pre-defined recipes (kind of process) and user defined customization (process tailoring) based on several types of coffee beans, different types of milk, special shots for flavoring, etc. In addition, processes can also be present in complex scenarios such as disease treatment, where doctors, nurses, patient and hospitals collaborate to deal with a sophisticated web of information that relates symptoms, diseases, treatment procedures and resource allocation.

Some processes are perceived as streamlined procedures (Fig. 1 - left example) that regulate and systematize each individual participation while indicating the required flow of actions and information. However, with the rise of knowledge-based industries such as financial, health care, software development and insurance, process participants are said to be knowledge-workers (KWs) that should be supported by a flexible computational infrastructure that do not constrain decisions at run-time. In such a modern industry, process execution depends on an intricate combination of context dependent information, emerging actions/tasks and collaboration (Fig. 1 - right example), where individuals take a special place as they typically use explicit but surely implicit knowledge to make decisions.

To capture the uncertainties found in collaborative, goal-oriented, knowledge dependent and non-repeatable processes, the process management literature brings the concepts of a different kind of process, usually known as Knowledge-intensive Processes (KIPs). In contrast with the traditional processes, perceived as streamlined procedures (i.e., structured), KIPs can range from partially structured processes occurring when the overall workflow is not explicitly defined, but the existence of policies and regulations supports the identification of structured fragments; to unstructured processes appearing when the participants define the activities to be executed.

KIPs represents an alternative to capture the complexity imposed by the knowledge-based industries, the unpredictability of modern individual-to-organization interactions aggregates extra complexity. In this scenario, achieving a goal may require KIPs to crosscut, be combined or be partially fulfilled, imposing process management techniques to extrapolate processes’ start-event and end-event boundaries to help process navigation and/or discover process trends and process anomalies.

This document is a living body of knowledge focused on Knowledge-intensive Processes (KIPs), its life cycle and how it can be combined with Workgraphs to improve process management. Workgraphs consists of the units of work (tasks, ideas, clients, goals, agenda items); information about that work (relevant conversations, files, status, metadata); how it all fits together; and then the people involved with the work (who’s responsible for what? which people need to be kept in the loop?), providing a flexible conceptual framework to address modern individual-to-organization interactions.

The remainder of this document is structured as follows: Section II presents the concepts of KIP; Section III briefly discusses KIPs representation; and Section IV describes the KIP life cycle and its transitions.

II. Knowledge-intensive Process

Knowledge-intensive Processes (KIPs) are everywhere but sometimes they are recognized as simple prescriptive processes (i.e., structured). However modern processes typically support individuals in achieving their goals and typically deviate from the original model to accommodate specific and unplanned needs (i.e., partially structured or unstructured).

Although this document adopts the term Knowledge-intensive Process (KIP), this kind of process is discussed in the literature through different synonyms, such as: Knowledge-intensive Business Processes (KIBP); Intentional Processes; Goal-Oriented Processes; Knowledge-Driven Processes; Decision-intensive Processes; Hybrid Processes; and Flexible Processes.

In this scenario, KIPs are processes whose conduct and execution are heavily dependent on knowledge workers performing various interconnected knowledge intensive decision-making tasks. KiPs are genuinely knowledge, information and data centric and require substantial flexibility at design- and run-time (VACULIN et al., 2011).

According to DI CICCIO et al. (2014), the main characteristics of KIPs are: Knowledge-driven; Collaboration-oriented; Unpredictable; Emergent; Goal-oriented; Event-driven; Constraint- and rule-driven; and Non-repeatable.

Some examples of KIP are found in literature, such as: Trip Planning; Incident Troubleshooting; and Fracture Treatment. In Appendix A of this document, some modeled KIP examples are provided.

III. KIP Representation

To represent real world scenarios, we can use process models. A process model is a way of structuring a Business Process Management (BPM), and indicates the elements that can be used as abstractions for organizing the process’s activities and to facilitate the understanding of their interrelationships. Process Models can be formal or informal. A formal process model precisely describes a flow of work and is typically executed using a Workflow Management System (WMS) or a Process Aware Information System (PAIS). On the other hand an informal process model is usually interpreted by humans and used as a discussion or documentation tool.

A process model can be represented with several languages or notations. Although most notations share some similarities and are capable of representing process abstractions such as activities, sequencing and decisions, there are conceptual differences between them. Some notations are activity-centric, where a process is composed of activities representing units of work, and control flow elements determine the order of activity execution. Others are data-centric, where a process progresses based on the availability of data and their values at a given point in time. Some examples of activity-centric notations are BPMN, YAWL, UML Activity Diagrams, Event-driven Process Chains (EPC) and Petri Nets, while the big exponent of the data-centric notation is CMMN. Both BPMN and CMMN are notations maintained by The Object Management Group (OMG) for modeling processes.

Another form to represent a Knowledge-intensive Process is through an ontology. Ontology is an explicit and formal representation of a shared conceptualization. It represents an unequivocal abstraction of reality, one that is comprehensible by humans for communication purposes. KIPO (Knowledge-intensive Process ontology) is an ontology proposed to precisely represent the concepts comprised in a Knowledge-intensive Processes and to identify all aspects involved within it. It was developed to describe KIP considering complementary perspectives, which were organized in sub-ontologies grouping relevant concepts of a KiP: Business Process Ontology (BPO), Collaborative Ontology (CO), Decision Ontology (DO) and Business Rules Ontology (BRO), integrated through a core ontology (KIPCO) that regard the essential attributes of a KIP. It enable a precise interpretation and a deeper exploration of all relevant concepts comprised within a KiP. KIPO argues that a KIP execution is driven by the agent intentions towards achieving the process objectives, and that the flow of activities (especially decision-making) within a KIP execution is deeply influenced by tacit elements from its stakeholders, such as Beliefs, Desires, Intentions, and Perceptions. This ontology is well-founded on UFO (Unified Foundational Ontology), a foundational ontology based on philosophic and cognitive theories.

This document illustrates most of the process models with BPMN (Business Process Modeling Notation) as BPMN is recognized as the de facto process modeling language. CMMN (Case Management Modeling Notation) is also used, as CMMN allows representing flexible workflows that can be called from BPMN process or executed standalone. Both notations, BPMN and CMMN, are supported by several tool vendors (SAP, IBM, BizAgi, Signavio, Camunda, etc.) and can describe formal or informal processes. It is important to mention KIPs may require other abstractions than those found in BPMN and CMMN as exposed in KIPO, but we will annotate the model when required.

BPMN

A BPMN (Business Process Modeling Notation) model allows representing activities that are organized in a workflow. Combining a diverse, formalised graphical notation with execution semantics in an interchangeable standardized format, it has since its release in late 2011 become an important standard for business process modeling.

The approach of BPMN is to represent the workflow directly in the model. It indicates through activities all possible states that a process instance can assume. Activities represent actions that can be executed by humans, external systems or other processes. The workflow indicates the sequence in which activities should be executed. To do so, the workflow may contain gateways to indicate conditional or parallel flows and loops.

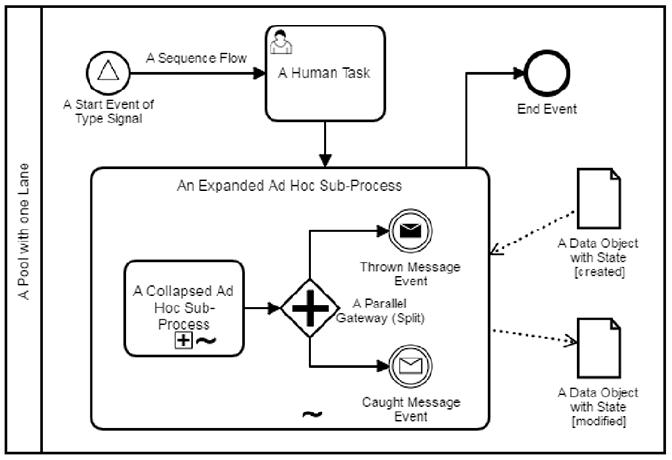

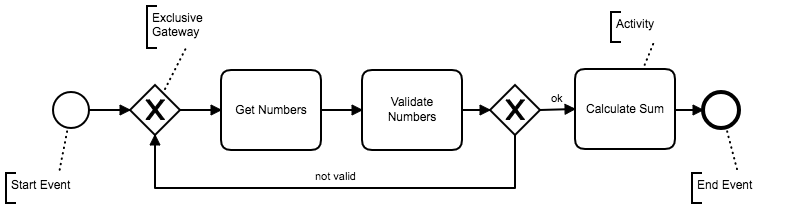

Fig. 2 shows the elements used in BPMN models, while Fig. 3 represents a example of a simple Addition Process starting with an activity (Get Numbers) to obtain the input numbers. Then the process validates those numbers (Validate Numbers) and moves on to calculate the sum (Calculate Sum) if the numbers are valid; if not valid, the process flow goes back to get new input numbers.

More information on BPMN models can be found in a quick guide here and in the official documentation here.

CMMN

Many processes are semi-structured, meaning that they describe work that is non-routine, so unpredictable. The structure of such a process depends on the specific case that is handled in the process. Applying BPMN (or other activity-centric notation) to semi-structured processes leads to problems, since its support systems cannot provide context information about the cases being processed and do not offer the flexibility that is needed to handle unexpected changes. Therefore, Adaptive Case Management (ACM) has been proposed to support such semi-structured processes.

ACM is an approach to support knowledge workers who need flexibility in handling their work. The term “case” is used in contrast to process to denote unstructured work, which is data-driven and highly unpredictable and therefore cannot be defined in advance. Knowledge workers need to be able to modify all aspects of a case at any time based on their knowledge and expertise. This is because the work conducted within a case is significantly based on decisions made on the fly by knowledge workers depending on the available data, the current circumstances and occurring contingencies. To comply with ACM standards, a model need to be able to support decision-making and data capture while providing the freedom for knowledge workers to apply their own understanding and subject matter expertise to respond to unique or changing circumstances within the business environment.

Data exchange is the center of attention in ACM. Data represent either the input streams in the Case Management process and the outputs of the Case Management tasks. By capturing data, what is really captured is knowledge about the case that is executed and experience that will be valuable to future similar knowledge work. In some extent, the system leaves its users (knowledge workers) free to prioritize the sequence of their activities in their own way, even to change it on runtime as there is great need to be agile and adaptive in these humancentric environments. Because of that, ACM is often linked to Knowledge-intensive Processes (KiPs), because a KiP is a business process whose structure and execution heavily depends on knowledge workers performing various interconnected knowledge-intensive decision-making tasks. Hence, ACM is considered to support KiPs better than BPMN.

However, ACM is not a modeling notation, but a paradigm, a collection of concepts and practices. The industrial interest in prospecting the potential of ACM led to a standardization process under the roof of the Open Management Group in 2014, resulting in a standard notation for ACM process models called Case Management Model and Notation (CMMN). Heavily influenced by an artefact-centric view of processes, the Guard-Stage-Milestone approach and the case handling paradigm, it aims to become a standard for case management.

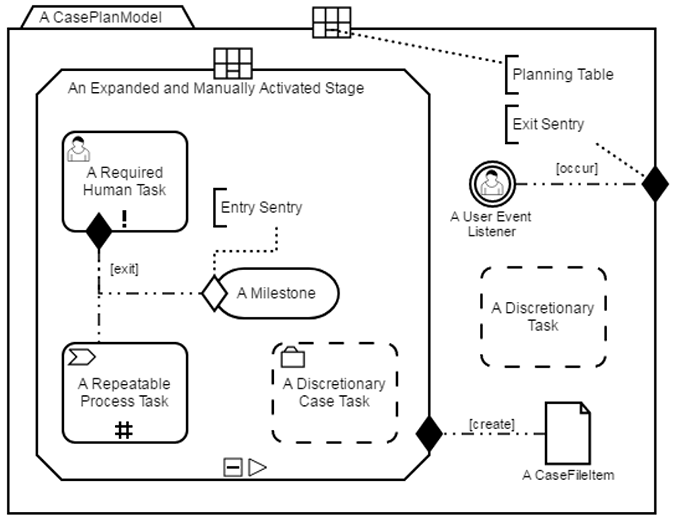

The main objective of CMMN is to define a common meta-model and notation for modeling and graphically expressing a Case. A Case primary involves tasks performed regarding a subject in a particular situation to achieve a desired outcome. The situation commonly includes data that inform and drive the actions taken in a Case. Besides representing activities likewise in BPMN, a case can contain discretionary elements that may or may not be executed. For example, a discretionary activity indicates such action is not mandatory to complete the process and may be skipped depending on the process execution context. Another important difference between BPMN and CMMN is how they represent sequences. In BPMN sequences are represented as directed edges connecting two model elements whereas in CMMN sequences can be modeled using connections and sentries (entry or exit criteria).

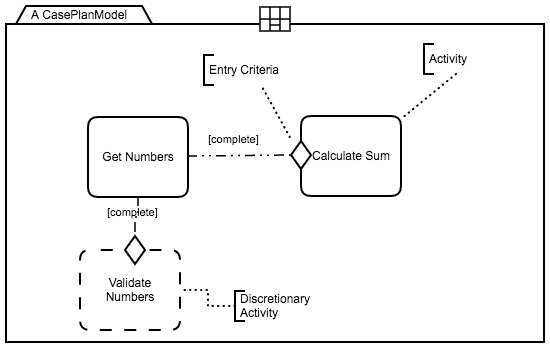

Fig. 4 shows the elements used in CMMN models, while Fig. 5 illustrates the same Addition Process using CMMN, where the Get Numbers and Calculate Sum activities are connected using a dashed-dot line and a sentry (shallow diamond). The dashed-dot line is decorated with the term complete and is combined with the sentry to indicate the Calculate Sum activity can only start when the Get Numbers activity is completed, thus representing a sequence. It also represents the activity Validate Numbers decorated with a dashed line to indicate such activity is discretionary. Different from the BPMN version of the Addition Process that uses a gateway to represent an optional flow, the CMMN model leaves the decision to apply or not apply validation to the case worker. As a result, when the CMMN version of the Addition Process process starts the Get Numbers activity will be available to execute but Validate Numbers and Calculate Sum will become available only when Get Numbers is completed. Given Validate Numbers is discretionary, the process may execute Calculate Sum without waiting for the validation action.

A nice explanation about the CMMN elements can be seen here and in the official documentation here.

IV. KIP life cycle

A life cycle is defined as “a series of stages through which something (such as an individual, culture, or manufactured product) passes during its lifetime”. Processes have life cycles as they are created, executed and in some way finalized.

A process life cycle can be seen as a collection of stages and associated operations that allow intra or inter stages transitions. A Process Stage can be defined as a place sharing common definitions such as a common metamodel or the same representation language. For example a Java program may seen as having two stages, one as the Java source-code and another as the Java byte-code. The Java source-code is defined by the Java grammar while the Java byte-code has it’s own file format.

Transitions can be defined as operations allowing concepts (files) moving from one stage to another (inter stage transition) or staying in the same stage with a different configuration (intra stage transition). Going back to the Java program example we can see the Java compiler as an inter stage transition as it compiles Java source-code into Java byte-code. On the other hand, a Java refactoring tool can be seen as an intra stage transition as the input and output files are both Java source-code.

Using stages and transitions abstractions to understand the life cycle for Knowledge-intensive Processes allows us to isolate and dissect concepts according to an specific rationale, and provide a didactic and systematic way to explore the phenomena. Moreover, stages and transitions abstractions are commonly used in Model Driven Engineering so we can leverage on some of its frameworks and tools.

KIP Stages

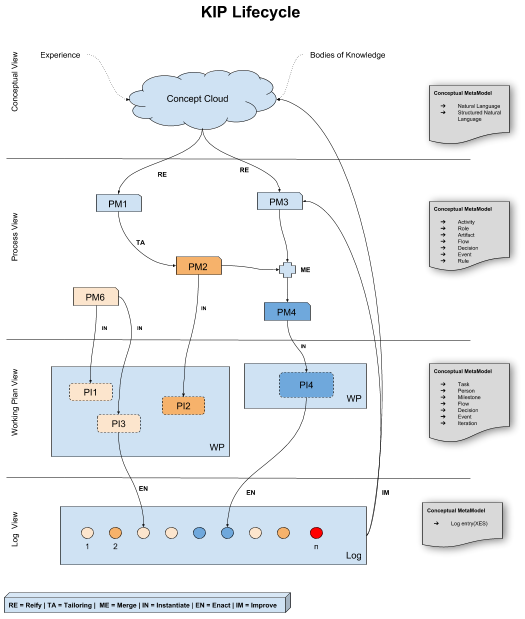

This section describes the four stages proposed in this document (Fig. 6): Conceptual Stage; Process Model Stage; Working Plan; and Log Stage.

Conceptual

In the Conceptual Stage, processes are experimented without paying attention to the representation language. Tacit knowledge is a big asset when performing Knowledge-intensive Processes. Although not explicitly materialized, tacit knowledge, which can also be seen as the experience of the worker, comprises one of the elements in the Conceptual View. Bodies of knowledge are also part of this Conceptual View. Examples of bodies of knowledge are knowledge bases, wikis, product reference manuals and documentation, and even maturity models or ISO documentations. Conceptual information can be either expressed in Natural Language or Structured Natural Language.

Process Model

In the Process Model Stage, the process is materialized using a formal representation language. Representing process models with a formal notation is important as it facilitates using several analytical tools such as model-checkers, quality assessment, workflow management systems, compliance monitoring, process mining, etc. Moreover, using a standard notation such as BPMN and CMMN promotes information sharing among the process community.

In this scenario, processes can be modeled and expressed into a set of activities and their dependencies. Processes are extracted (reified) from the available concepts (Conceptual View), and created according to the methodology of the process defined. Processes have information such as the activity name, role, artifact, flow, decision, event, and rule.

- Activity is the identification a piece of work that needs to be performed when executing the process.

- Role is the identification of which department, person or external parties are responsible for the execution of the activities.

- Artifact is the data that can be used as input or is the output of each activity.

- Flow is the direction of the activity. It indicates whatever occurs before and after each activity.

- Decision is when there is the need to act upon occurrences that are optional. It can either result in the execution of an activity, or multiple activities, as well as it can lead to another decision or artifact.

- Events are instant occurrences in the process. They usually have a cause and an impact.

- Rules can be defined as the constraints that processes should consider when executed.

Processes’ activities can be tailored or merged. Tailoring means it is possible to customize a process for a specific instance execution on the next stage - the Work Plan - and merging means it is possible to execute two or more process activities at once. Merging activities also means changes will occur from this stage of the life cycle on.

Working Plan

In the Working Plan Stage, the process model is instantiated into several different instances. hese instances can also be seen as each time the process is executed, totally or partially. At this stage, workers can work on specific chunks of tasks that have information such as their own due date, for example, and are part of a bigger project plan.

In this scenario, the moment process activities, methodology, technical tacit or explicit knowledge are represented by chunks of work meant to be done. One process model generates one or more work plans. A working plan has information such as task, person, milestone, flow, decision, event and iteration.

- Task is a chunk of executable work.

- Person is whoever is responsible for working on that task. This person should also be responsible for communicating occurrences while working on each task.

- Milestone is the goal that a set of tasks is supposed to reach.

- Flow is the indication of which task is executed before and which task is executed after a task.

- Decision represents the decision-making associated with processes and cases (e.g., business decisions and business rules).

- Event is something that happens during the course of a flow.

- Iteration is each set of tasks that can produce a minimum deliverable. The tasks to be executed in each iteration are selected at total discretion of the project manager and team, according to what’s been agreed with the client/stakeholders.

Communications, task length definition in this stage depend on people, which makes the process vary according to decisions made when either planning or executing a task. What information is relevant to a person can also vary. These characteristics of Knowledge-intensive Processes are evident at this stage.

Log

In the Log Stage, logs are generated for each step of the instance execution, called enactments. Whether each chunk of the instance is created or edited, modifications will be logged. These logs enable future analysis on how much compliant the execution was in regard to the process model.

In this scenario, when each task is executed, e.g., a person performed the work described in a task, the task is updated with information regarding the execution. Information such as date and hour of completion, who was responsible for completing the task, and all sorts of information can be collected regarding a task and its workflow. Logs allow the identification of repetitive patterns during execution, which can become improvements in the process.

KIP Transitions

Although using standard processes result in positive outcomes such as predictability, performance and reliability, different businesses and environments might have their own specific requirements. To comply with these differentials, a standard process might need to endure minor changes. These changes can be reification, tailoring or merging processes and/or its activities. In other words, a process suffers adaptations in order to comply with specific needs of organizations or projects.

Each of these adaptations can result in one or multiple process transformations. These transformations are specific and different throughout each stage change. Also, processes can suffer instantiation, enactment and improvements, even when they are not necessarily changed between stages.

This section describes the five transitions proposed in this document (Fig. 6): Reification; Tailoring; Instantiation_; Execution/Enactment; and Improvement.

Reification

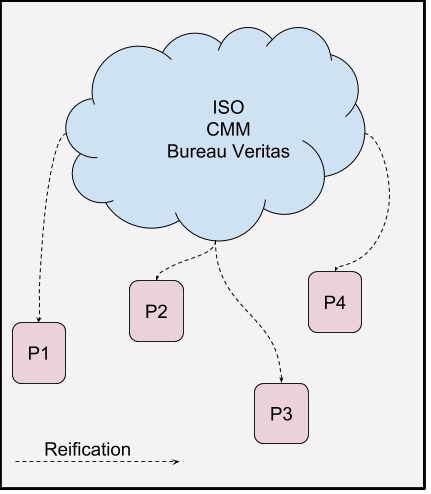

This transformation represents when the concepts from the Conceptual View are transformed in processes. This means this process will now have a starting point, a flow, indications of responsibilities for groups of process activities, i.e., will have incorporated the structured elements that belong to the Conceptual View. The figure below illustrate the Conceptual view as a blue cloud with some concepts. All 4 processes (P1, P2, P3 and P4) are reified from the concepts in the cloud. These are definitions coming from and based on extensive research and best-practices on software development. The concepts in the cloud are typically represented in natural language or non-formal representations, which demands an expert to transform these concepts in processes (reification).

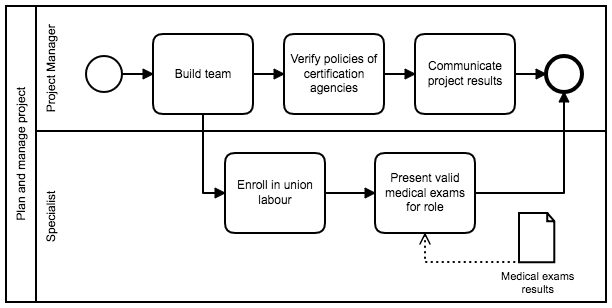

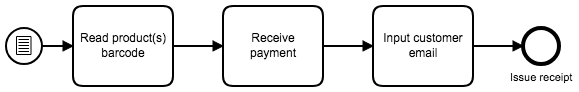

Let’s try to make things clear with an example, represented in BPMN. Let’s suppose a project manager is defining tasks for a project, and she/he gathered some concepts with the company’s VP after a long meeting. The new reified process can be something like:

If at this point you’re thinking “this is really hard to predict and it’s a very creative procedure”, guess what? You’re so right!! And I don’t mean to be mean, but there’s some other aspects to consider such as time, team expertise, budget, technologies… None of these were in the conceptual view, right? That is why there are other transformations that are very likely to happen. Next topic will demonstrate the next one :)

Tailoring

Processes may need to be modified to comply with business or environment needs. These modifications are called tailoring. In other words, a main established process will be adapted when running certain instances. For example, if one project of a company works with hazardous materials, this project might need to run different steps in order to comply with safety obligations, but at the same time, this project also runs the main established organizational process. One of the modification operations a process can experience is Merge. This means two or more process activities can be merged into one.

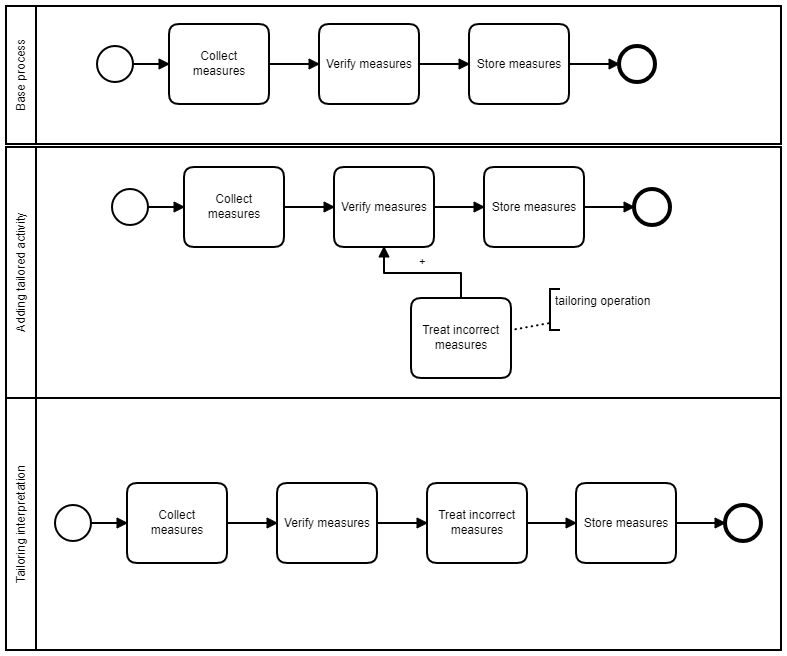

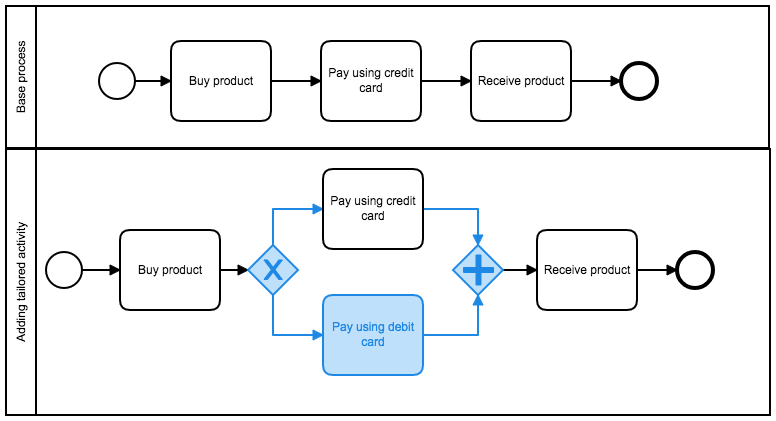

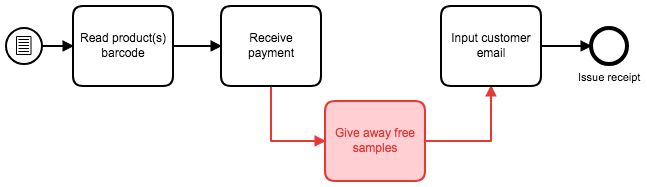

As an example, let’s suppose a worker has to collect, verify and store measures (e.g., size and weight) of parcels that are supposed to be mailed to clients, so a system can forsee delivery expenses. A simple example using a common notation (BPMN) is shown below.

After posting all parcels in the post office service, some prices may vary. The original process does not consider that measures and prices might have to be updated. A tailored process to include this unforeseen activity is illustrated below. One process activity was added to the original process.

Another example is when an online store starts accepting debit as payment method for centain cases (for example, if a client purchase is over $100). Then, the debit card option has to be added to the process. This can be done using Tailoring. The blue elements below are the elements that were added during this process tailoring.

Instantiation

Instantiation occurs when processes become executable chunks of work and a working plan is materialized. It is the transformation between process and actual work plans. The process is defined and every time the process is executed, entirely or partially, it generates a new instance.

Execution/Enactment

Improvement

After enactment, logs of each process and instance execution are recorded. Analyzing these logs, looking either for pattern repetition or activities not executed, can be used as input to process Improvement.

References

Appendix A. KIP Examples

In order to better understanding the KIP phenomenon this section brings some examples to expose how this kind of process are in fact complex and non-deterministic.

| Process | Description |

|---|---|

| Trip Planning | Process that aims to support a traveler to plan a trip. |