Trip Planning Example

Scenario

Planning a trip is a recurring endeavor that usually requires the execution of a set of activities, such as:

- Defining the itinerary;

- Defining the start and end dates;

- Deciding on the number of travelers;

- Booking the airline;

- Booking a place to stay;

- Reserving a car;

- Reserving attractions;

- Buying insurance.

To facilitate this procedure the traveler might just set the initial parameters (itinerary, dates, travelers) and negotiate everything with a travel agency or buy a pre-packaged trip (what is the fun in that?).

A more intrepid traveler might enjoy the do-it-yourself approach and spend hours - possibly days - navigating on several websites to better understand the options available, and create a bespoke traveling experience. However, dates may be flexible and travelers want to fly on cheaper flights. Maybe the itinerary is flexible and travelers want to explore local hidden gems. Maybe after talking about the travel plans on a family Sunday lunch, Grandma decides to jump in!

TODO list

In order to organize and control the Trip Planning Procedure the intrepid traveler may create a simple TODO list to expose the activities and associated information required to complete the plan. The list might be executed as per the traveler’s discretion but some rules must be followed such as setting the initial parameters (itinerary, dates, travelers) upfront. Fig. 1 brings a BPMN (Business Processes Modeling and Notation) process model to represent the TODO list in a “sophisticated” way.

Besides representing the activities, Fig. 1 process model attempts to expose a streamlined flow, connecting activities from the process starting point (Start Planning Trip) to the process endpoint (Travelers Ready to Travel). The rationale of streamlining the activities to plan the trip is to define a systematic manner to reach the process goals while making the traveler more efficient and effective. However, defining such flow seems complex: What should be done first? Reserve the Place? or Reserve the Airline? How may times can the same activity be executed to accommodate new demands? How to incorporate the activities related to the supporting IT infrastructure (e.g. airline websites, credit card authentication, etc.)?

A simple answer to these questions is: The flow of activities depends on the traveler’s context. The traveler’s context may be simple if the traveler is traveling alone, to a single destination. In this scenario the traveler might be able to make straightforward decisions thus executing most of the activities once, without requiring following a complex process model with several gateways, loops and messages. On the other hand, the traveler’s context may be complex, involving several travelers with different needs (remember gramma!) and multiple destinations, which brings issues related to collaborative decisions. This complex context may require several loops, gateways and peer reviews to make sure most of the needs are met. As a result, creating a one-model-fits-all seems unproductive, if not impossible. Still, one can argue the model may be created by a trip planning expert but it is important to understand the intrepid traveler is a knowledge worker with a sophisticated decision making attitude who is capable of tweaking the trip parameters to achieve a better goal, and forcing a pre-established flow of activities may hamper reaching this goal.

KIP modeling

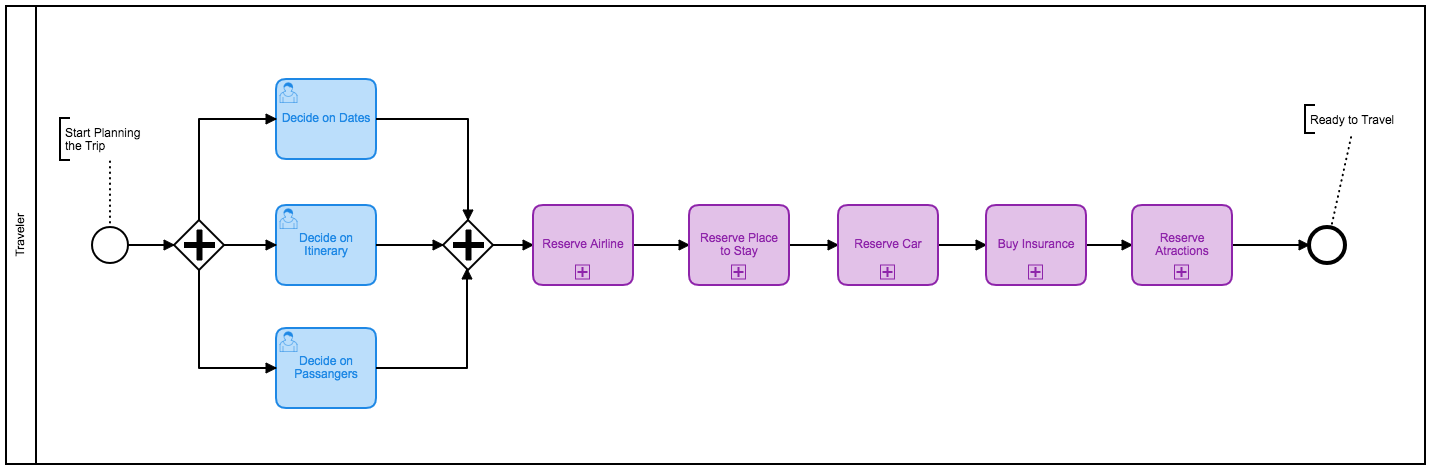

A better way to represent the Trip Planning Procedure is using the Knowledge-intensive Process concepts where the process model may indicate an accepted flow of activities, but the traveler is free to combine the activities to fit his/her needs. For example, Fig. 2 illustrates a simple flow where the traveler decides on the initial parameters, then he/she deals with the airline, hotels, car, insurance and attractions sequentially. The process model is then used as a guide to help the intrepid traveler understanding what needs to be executed to plan the trip.

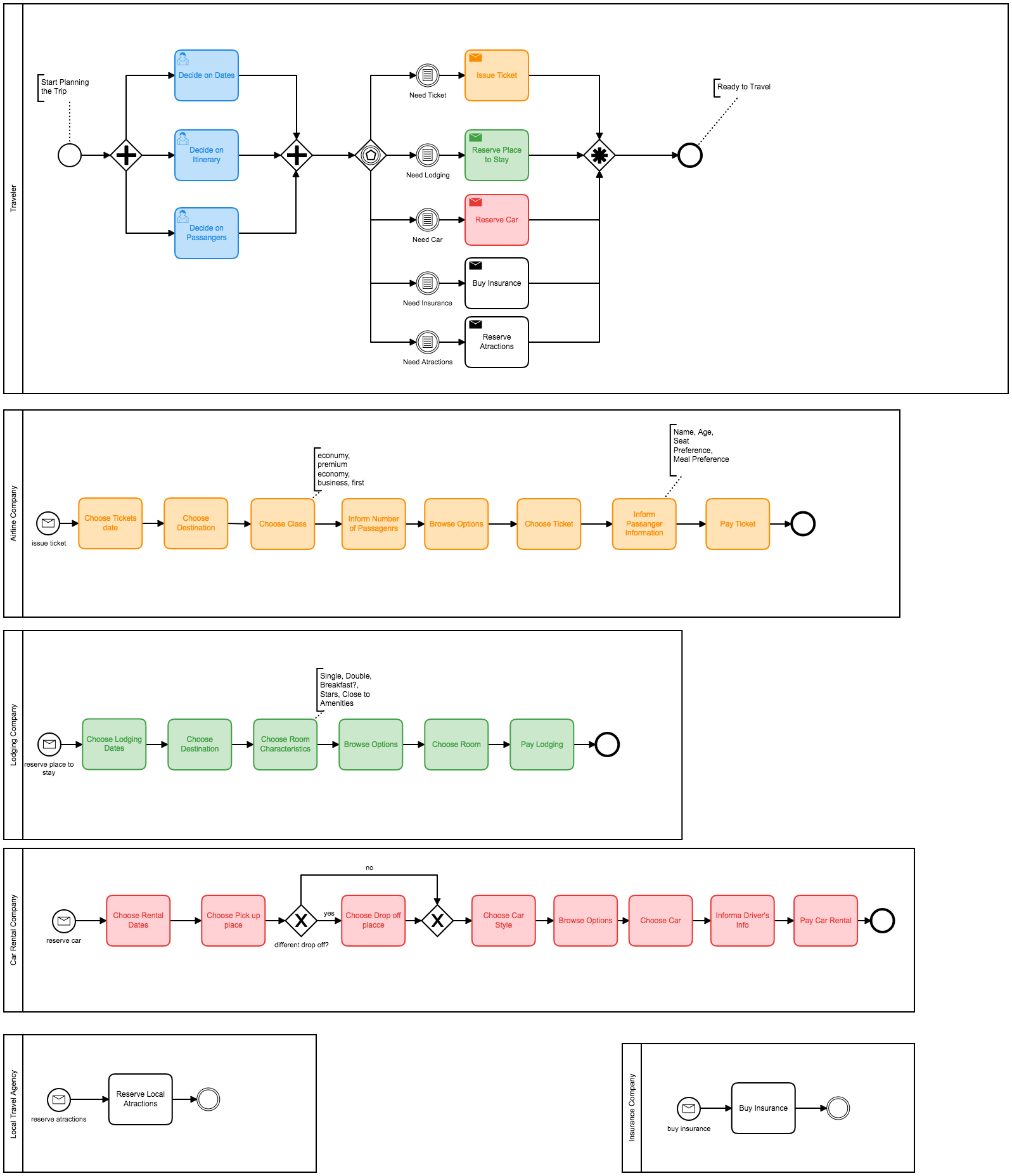

A further look at Fig. 2 exposes some activities (the purple ones) have a ‘+’ sign at the bottom indicating the activity is in fact a process itself, sometimes with several nested flows. For example, to Reserve the Airline, the traveler needs to choose the class (first, business, coach), the seat (window, aisle), the food (vegetarian?) and also pay using a credit card (or miles). It is easy to imagine the whole Trip Planning Procedure may require executing dozens of different activities, some human based, some hidden by the IT infrastructure. For example, Fig. 3 exposes a more complex process involving several companies illustrated as pools and messages sent from the travelers side. This complex process model may be straightforward to follow based on the adopted coloring scheme or given the messages used to trigger the corresponding process start-events have the same names. However, the complexity can be noticed as the model brings a multitude of different modeling elements (lanes, tasks, messages, gateways and start-events) and also starts dealing with complex collaboration patterns. It is important to mention this process is still far away from being realistic as it does no contain decisions (gateways), data objects, error-handling or IT related tasks.

Enactment and improvement

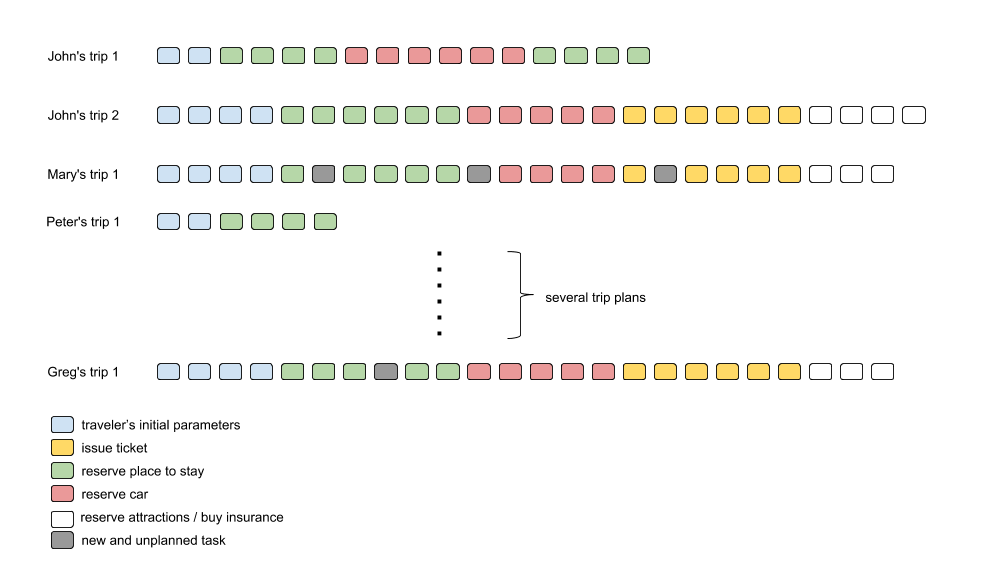

At the end of the day, our intrepid traveler may end up executing dozens of tasks depending on his/hers particular context. Moreover, planning a trip is a recurring procedure and this process model may be enacted by different travelers, sometimes sharing the same context and following similar flows. The resulting log illustrated by Fig. 4 exposes traces with the tasks executed by each traveler. For example, Traveler John enacted the process twice (planning two trips) and Traveler Greg enacted the process once. The differences between each trace indicates it may be hard to impose a prescribed sequence of tasks, even if the process engineer considers all travelers managed to reach the process endpoint and skip representing specialized escape flows. It is also important to point out traces do not only differ based on task sequences but also on unplanned tasks. Unplanned tasks (gray nodes) occur when a traveler executes a task that was not part of the original process model, indicating the process model may be incomplete and did not fit well to the travelers context.

In this scenario, some complex questions arise: How to keep track of my progress? How to pass on a Trip Planning Procedure experience? How to learn from planning several trips? How to avoid recurring mistakes/problems? How to combine several trip planning experiences? and recommend the most successful ones? What if someone needs to execute an unplanned (not defined in the TODO List) activity? How to access the information one need at the proper time?

Other than these questions raised, there is a list of activities (that certainly are part of the process) to think about that were not mentioned such as:

- Check baggage allowance (weight and sizes can prevent you from getting that boat transfer or that low cost airplane ticket);

- How to build and communicate your travel plans when you’re in a group;

- How to share expenses? The hotel room for 4 people, or the uber someone paid;

- Currency exchange;

- Airport transfers;

- Documents checklist (visas, permits, etc);

- Flight upgrade rules;

- Long layover (what can I do with these few hours I have in Rome?);

- Loyalty programs;

- Trip overall budget planning.